Conservation visionary Captain E.V (Val) Sanderson devoted much of his life to preserving Aotearoa New Zealand’s unique flora and fauna. Judith Galtry profiles this tenacious and committed man, a one-time resident of Paekākāriki, where he restored his property to native bush and from where he could keep a keen eye on Kāpiti Island’s burgeoning bird population.

“Captain Sanderson’s vision was realised on his own land, but he also worked to realise it throughout New Zealand.”

In its obituary to Captain Sanderson in 1946, Forest & Bird noted:

“The easy way held no attraction for him,” writes Forest and Bird magazine in 1946, “and on dry, barren sand dunes at Paekākāriki he demonstrated his ability by transforming them into a patch of native bush. Many of these trees are already assuming forest status, an effort which is considered by some to be little short of a biological wonder. He proved at his home at Paekākāriki that native trees could be grown on a sand dune and the beautiful native tree plantation that he established is today a monument to his efforts.”

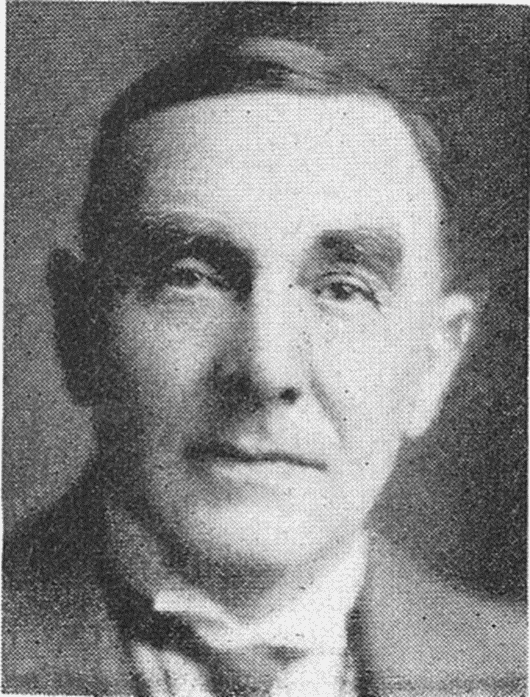

When Captain Ernest Valentine (Val) Sanderson, founder of the New Zealand Native Bird Protection Society (now named Forest & Bird) died in 1945, the Society’s tribute ran the headline ‘Sanderson: The Indomitable’. No description could have been more apt for a man of such immense purpose and determination with a strong fighting spirit that he turned to the benefit of conservation in Aotearoa. Driven and single minded, Captain Sanderson was instrumental in creating Kāpiti Island as a nature reserve.

Captain Sanderson (or ‘The Captain’, as he liked, even insisted, on being called) lived in Paekākāriki (1930-1945) for the latter, and seemingly most settled and happiest part of his life. This included for the entire tenure of his role as President of the Native Bird Protection Society (1933-1945); the society he had helped create in 1923.

His cottage with its peaked roof and surrounding bush, resplendent with native plants and birds, sits on the eastern curve at the top of Paekākāriki’s Pingau Street where it forks southwards. Ironically, Captain Sanderson – worshipper of native plants and respectful of Māori conservation practices – ended his days in a Paekākāriki street with a seemingly misspelt Māori name: Pingau Street.

Most of the trees were planted by Sanderson himself almost a century ago to test whether natives could thrive on seemingly inhospitable sand dunes. The very success of his experiment has meant that his house, built sometime around 1930, has remained hidden away and shrouded in mystery.

But this is also the story of a man with a colourful and turbulent past. At the age of 27, Val was involved in the violent death of his father in Wellington. He went on to serve in two wars. His first marriage ended in estrangement and later was dissolved on the grounds of desertion and failure to provide financial support. But more on this later.

Sanderson’s conservation work was rewarding, but it was also fraught with contention, something he did not shy away from and even seemed to embrace. It was only much later in life that Val found fulfilment with the establishment of his Paekākāriki house and garden, along with his second marriage to his much younger wife, Nellie Milne, and the birth of their two daughters.

Sanderson recognised the uniqueness and interdependence of Aotearoa’s flora and fauna. An environmental polymath, he was interested in re-establishing native plants and birds; restricting the introduction of species, such as weka and kiwi (of which there are many different types), to habitats where they had not previously lived so as to prevent interbreeding and disease spread; eliminating the use of lime to catch wild birds, as well as working to restrict the activities of the acclimatisation societies of the time.

On the road outside what was once Sanderson’s cottage the sound of birds attracted by the sheltering canopy of native bush is loud and enthralling. Kererū and tui swoop across to feed and nest in the bush garden. Paekākāriki’s bird life is drawn to his native garden, also encouraged by the conservation efforts that he contributed to on nearby Kāpiti Island.

Having walked past the Pingau Street cottage for almost forty years, I have only recently become aware of its intriguing past. Most Paekākāriki locals with whom I have spoken are similarly unacquainted with the existence and rich legacy of Captain Sanderson and his native garden..

Reflecting Sanderson’s strong interest in Māori culture, an ornate and mysterious green gate reminiscent of a pātaka (Māori storehouse)) stands at the entrance to the property. A photo taken in 1936 suggests the gate has remained the same since Sanderson’s time, when it was known as the Māori Gateway to the Sanderson Bush. According to his daughter, Nancy Jordan, her father was ahead of his time. ‘He felt the world should be in a natural state if it was to survive,” she told Forest and Bird in 2013. “He admired the Māori – that they could live with nature and respect it.”

An Unsettled Early Life

Ernest Valentine Spreat was born in Dunedin on 8 February 1866, the second of five children of Jane Sanderson and William Walter James Spreat. By 1874, the family had moved to Wellington, where Val attended Wellington College and was later employed as a clerk by the Australian Mutual Provident Society. The family lived in a two storied house in Wellington’s Mt Victoria.

His father, William Spreat, took early retirement from his job as a lithographer in the Government Survey Department, due to worsening epilepsy. Over time, he became increasingly irritable and reliant on drink, sometimes threatening his family. The family separated for a time and Val took on his mother Jane Sanderson’s surname. On his own entreaty, his father returned, but lived apart from the family in a stable. In the period leading up to his death, Spreat experienced more frequent convulsions and a deteriorating mental state. In July 1893, he grabbed a knife and attacked his sons, Louis and Val, for not carrying out his request that they clean around the Pirie Street property where a clay bank had slipped onto the footpath. Tragedy ensued with the oldest boy, Louis, shooting his father in alleged self-defence.

Initially, the injury seemed not to be serious, but Spreat went downhill over several hours and died late that night. As he lay dying, he signed a statement absolving Louis, claiming the shooting was his own fault. Louis was charged with ‘wounding with intent’. A coronial enquiry into the death took place at the Cambridge Hotel. Val had to testify. In his testimony, Val claimed that he had seen his father “be violent before, but never so violent as he was on Saturday” and he had “felt perfectly certain at the time of this occurrence that Spreat had gone mad, and was in terror of him.” On 14 July the coroner’s jury returned a verdict of ‘justifiable homicide’. Spreat had left his property in his will to the family.

Unsurprisingly, this incident made national headlines and featured in most regional papers. Headlines at the time referred to: ‘The Wellington Shooting Affray’; ‘Remarkable Shooting Affair’; ‘The Wellington Tragedy’ and ‘Tragic Occurrence’ to name but a few. Chris Maclean in his book Kāpiti speculates that the ensuing notoriety may well have influenced “Val’s aggressive behaviour in later life, and his mistrust of others.”

In 1900, when he was in his early thirties, Sanderson enlisted for service in the Anglo Boer War (South African War). He went on to fight in World War One, reducing his age by several years in order to enlist, but was repatriated early and discharged ill. Henceforth, he was known as Captain Sanderson; a significant departure from his given name of Ernest Spreat, perhaps affording him greater confidence to shape his own destiny.

The eventual settlement of his father’s estate gave Val the means to finance a partnership in a business, Magnus Sanderson and Co, which initially imported bicycles then cars.

His first marriage to Emily Louisa Cooper took place in Lower Hutt on 6 January 1904. They had no children and eventually became estranged. In 1921, a divorce was issued on the grounds of Sanderson’s ‘alleged desertion’ nine years earlier, with Emily claiming she had kept herself since then.

Sanderson’s divorce and the selling of his partnership in the motor trade both occurred after his return from WW1. From then on, he determined to devote his life to conservation, relinquishing a regular income and refusing a war invalid pension so he could remain independent in his advocacy efforts. Looking back on this period, Sanderson reflected (as cited in Macleans’s Kāpiti, “Being alive to the fact that the accumulation of wealth should not be a man’s sole aim. I retired from active money seeking early. At the same time an idle life without aim or object did not appeal to me, and, moreover, it seemed that a man should do something for his country to warrant his existence.”

A Passion for Conservation: Kāpiti Island

Sanderson’s main joy and sense of purpose derived from his conservation work on Kāpiti Island.

In 1897, the island had been made a forest and bird reserve under the Kapiti Island Public Reserve Act. Sanderson had initially visited the island in 1914 and was appalled to see how little had been done towards protecting its flora and fauna from introduced species. On revisiting the island in 1921, he found that the reserve area remained unfenced, with sheep and goats continuing to strip the bush. Following this visit, Sanderson set out to embarrass the Lands Department responsible for the island’s upkeep, through a newspaper campaign.

In 1922, Captain Sanderson wrote about the plight of Kāpiti Island in New Zealand’s Forest magazine:

“We have robbed the birds of tremendous areas of bush on the mainland. Are we not patriotic enough to give them a last, secure resting place on this small island, seven miles by one mile in area, in order that our children and our children’s children may see what New Zealand was really like when their daring forefathers first set foot in this land of ours?”

As a direct result of Sanderson’s advocacy, the Government took steps to have the Māori-owned portion of Kāpiti Island fenced to keep out cattle and sheep, thus dividing the sanctuary and the farmland; hired a possum trapper; and appointed a caretaker to eradicate the wild goats. It was these initiatives that allowed the island to return to its natural state as a bird and forest sanctuary.

Although he was against introducing native species from other parts of the country to Kāpiti Island, he could be inconsistent. The then ranger’s daughter, Sylvia Wilkinson, wrote revealingly about visits to the island by The Captain and his canine companion, Mack:

“Captain Sanderson turns up from time to time to see how things are going, bringing with him a large setter, Mack. Dad disapproves of a dog being brought on to the sanctuary, but what can one say to the President of the Bird Protection Society? The Captain is not pleased when told he can’t have Mack inside the house but that he must be kept tied up outside.”

Meanwhile, the ranger’s wife was desperately searching for their weka, fearing it would be driven off the nest by The Captain’s dog just when her chicks were due.

In 1975, thirty years after her husband’s death, his widow, Nellie Sanderson, who was still living at 15 Pingau Street, noted that while her husband’s “main goal was to increase New Zealanders’ awareness of the uniqueness of their natural environment, his biggest satisfaction was having foraging animals removed from Kapiti Island.”

Over the years, Val spent much time on Kāpiti Island. Returning to the island 70 years later, his daughter, Nancy Jordan, recounted an unforgettable family visit to the island in 1940 when she was three years old. The Sandersons were to spend a week with the Webber family at their home at the northern end on Waiorua Bay. Utauta Webber had gone to the mainland to buy supplies for the visit when bad weather sprang up and the Sandersons were stranded on the island for three weeks. Fortunately, her father “was a good survivalist, killing a sheep and fishing and eating from the local vegetable plot.” On this visit, Nancy also saw mature Pohutukawa which had been planted by her father decades earlier.

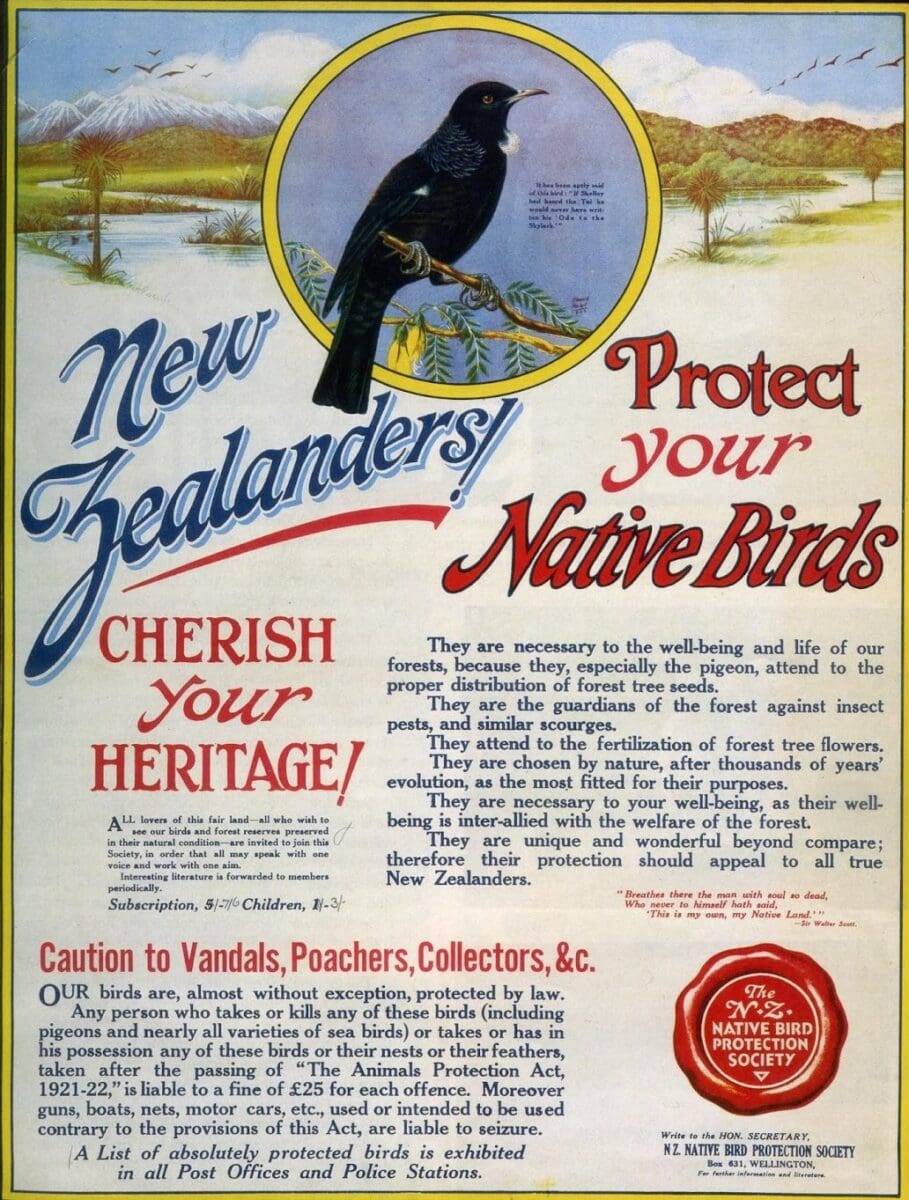

Founding of the New Zealand Native Bird Protection Society

The Kāpiti Island campaign was a significant achievement for New Zealand’s emerging environmental movement. Encouraged by its success and recognising that New Zealand was just a larger version of Kāpiti Island, Captain Sanderson set out to promote native species’ protection nationally. Along with former Prime Minister and conservationist, Sir Thomas McKenzie, he founded the New Zealand Native Bird Protection Society on 28 March 1923, at a well-attended meeting in Wellington. Although initially serving as Secretary and Treasurer with McKenzie as President, it was generally acknowledged that Sanderson was the driving force behind the Society.

On 31 March 1923, Sanderson gave an address on the Society’s formation, which was reported in the Evening Post. In this immediate post-war period, when many New Zealanders were still grieving loved ones lost in WWI, his patriotic tenor doubtless struck a chord.

“Why, some people ask, does Captain Sanderson go to all this trouble over birds?’ said the lecturer [Sanderson himself]. “The reply is,” he said, “that our soldiers in their sentiments and songs amidst the oven like heat of Egypt and the mud and cold of France turned much to their bush and birds in far-off New Zealand. They almost saw the rushing-stream midst the waving tree-ferns; they almost heard the fluff-fluff of the lazy forest pigeons as they flew, from limb to limb of the trees; they almost saw the tui perched high up in the towering rata tree…But now, alas, it sometimes seems that this fair country is in danger of being destroyed by the ignorant and the vandal, equally as it might have been destroyed by the enemy we fought so hard to exclude.”

In 1933, Captain Sanderson himself took the position of President of the now thriving Society; in 1935, renamed the Forest and Bird Protection Society of New Zealand. From then until his death, he dedicated most of his time to the Society. And what an asset he was: a virtuoso of spin, an astute political lobbyist and media influencer, as well as skilled in educating the public about conservation.

But, over time, Sanderson became increasingly isolated, falling out with several key figures in the conservation world. This included, for a period, the ranger on Kāpiti Island over the progress of the possum eradication problem and the introduction of bird species not native to the island. It was no secret that Val could be prickly and temperamental.

But he was also generous with his time and knowledge. He accepted invitations to give nature talks, including at scout camps where refusing offers of transport, he came “trudging in carrying his little haversack.” When former Forest and Bird secretary, Mr. D.A. McCurdy, came back from WWII to live at Paekākāriki he was “taught beekeeping by Captain E. V. Sanderson.”

In 1932, Mr. R.A. Anderson, President of the Native Bird Protection Society, noted that from its inception Captain Sanderson had ‘given all his time to the work of the society, and I doubt if there is another official connected with any society in New Zealand who has given free services in the public interest to the same extent.’ This commitment continued until his death in 1945.

The Purchase of a Paekākāriki Perch

Around 1929, Sanderson purchased a patch of bare land on a hillside in Paekākāriki’s Pingau Street overlooking Kāpiti Island. Initially, he pitched a tent on the land, followed by a small whare where he lived until his house was completed.

Paekākāriki was close to Wellington where he continued to work three days a week, while offering respite from his often-contentious advocacy work. Importantly, the section faces Kāpiti Island, a view later captured from the cottage’s living room window. From here, he could monitor, with binoculars, the various “to-ings and fro-ings’ from the island, including the shipping from Wharekohu at its southern end of wild sheep that had been rounded up from the island’s reserve.” According to the then local paperboy, Geoff Roberts, his Pingau Street eyrie also enabled The Captain to operate “his heliograph to flash a signal to the caretaker on Kapiti Island to let him know what native birds were stopping over at his big bush reserve around his house then flying over to the bush clad ranges at the back of Paekākāriki Hill.”

By 1933, when he assumed presidency of the Native Bird Protection Society, Sanderson was nearing 70 years of age. By then he cut “a craggy, rather stern figure.”

But Sanderson’s age and sometimes difficult personality had not diminished his chances in the marriage market. On 10 October 1934, he surprised many people by marrying Nellie Milne, more than 30 years his junior. They went on to have two daughters. Nellie was also an aunt of the late Paekākāriki plumber, the suitably named Neville Leak.

In his book Kāpiti, Chris Maclean notes that at this point in his life, having become alienated from many key figures in the world of conservation, Sanderson dedicated himself to developing ‘his own sanctuary’ at Paekākāriki.

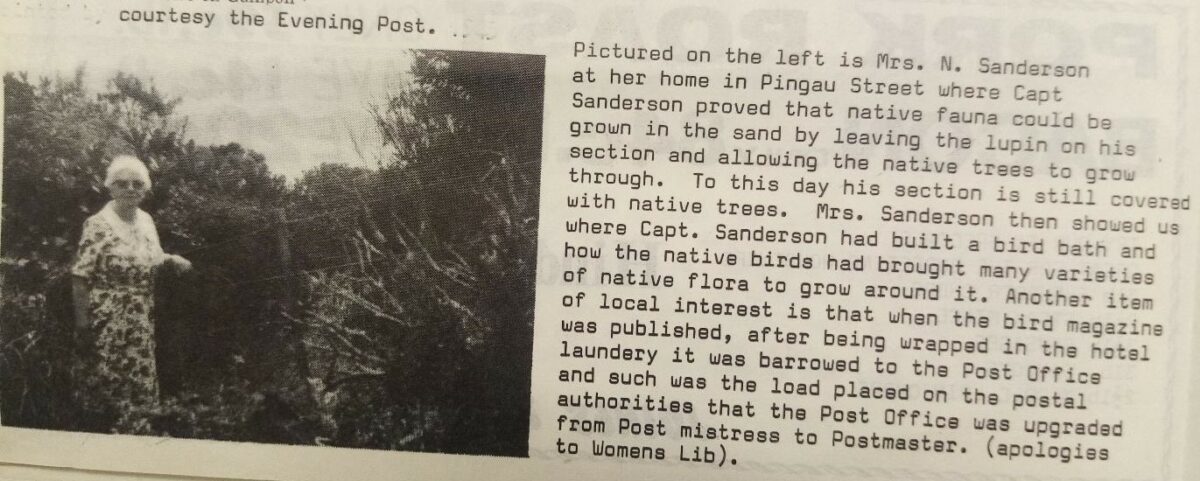

Sanderson was determined to transform his bare Paekākāriki sand dune into a native bush preserve to demonstrate this could be done. Many people dismissed his scheme. According to his widow, “The neighbours laughed and said it would all be destroyed by the first big winds.”

Single-mindedly, he set out to prove his critics wrong. Among the natives (about 70 species) that he planted which became strongly established were “poroporo, wharangi, taupata, makomako (wineberry), kotukutuku (commonly called ‘konini,’ which is the name of the sweet berry), koromiko, ngutukaka (kakabeak), pukanui, taraire, karamu, rata, karaka, karo, ngaio, whau, taupata, ake-ake, pohutukawa, ti-toki, tarata, ti (cabbage-tree), mamaku, (a tree-fern), puriri, mahoe, kawakawa, manuka, whauwhi (lacebark) and patete (fivefinger).”

Sanderson’s success in establishing a native forest on an exposed sand dune attracted nationwide publicity. A 1936 newspaper article notes, “Proof of the falsity of a widespread belief that native trees of New Zealand are very slow in growth and difficult to establish is given abundantly on a half-acre section at Paekākāriki, Wellington, which Captain E. V. Sanderson began to plant only 10 years ago…A dreary stretch of sand-dunes, covered with lupin, exposed to strong winds from the sea, has been changed into a delightful young forest. By intelligent handling, the plantation, which contains a very wide selection of native trees, has attained a general height of 15ft to 16ft.”

To detractors, the half-acre section became “known as ‘the rubbish-heap’ because of the heaps of dead lupin and other rotting vegetation, destined to form the humus necessary for the young native seedlings.” In the end, they were forced to concede that Captain Sanderson’s vision was well founded.

In 1941, a mere eleven years after Captain Sanderson had begun his planting programme, the forest was flourishing.

Sanderson called his Pingau Street home Te Kohanga (The Nest). Restoring a healthy native bird population in Paekākāriki was central to his vision. Paekākāriki’s paperboy, Geoff Roberts, described The Captain’s property as enclosed by a “high wire netting fence to keep cats, stoats, and weasels out. Even the gate was netting right to the base of it”’ The fence also protected three plump wekas, which Sanderson had obtained by permit to address the wood-lice (slaters) problem. His weka strategy was effective. “Within a week of the birds’ arrival all plants began to improve in health. Slaters, snails and other pests suffered very heavy casualties – and the wekas waxed fat.” Plants which the woodlice had previously reduced to bare sticks were now flourishing.

There was always a dish of food for birds during early spring and winter at Te Kohanga, although Sanderson ruefully observed, “My only grievance is that the birds partake of my good fare during the winter and when summer and spring arrive, leave to eat other people’s grubs.”

Sanderson’s bird tales, including his story of a red-billed gull wounded by a Paekākāriki lad’s pea rifle, attracted much publicity:

“The gull had an injured wing so Captain Sanderson took it home to nurse it back to health,” reported the Evening Star in 1937. “The gull would wander around the house as if it had been born and reared there. Captain Sanderson says that the bird was an astonishing expert in catching blowflies. If it was standing in the drawing room and a ‘bluebottle ‘flew near it would make a dart and a snap that never missed. This keenness of eyesight and nimbleness were also shown in another feat. The bird was very fond of cheese. If a piece of bread was held up and dropped, the gull took no notice; it merely seemed to be bored; but if the morsel was cheese it was neatly caught in mid-air and was quickly gobbled. Eventually the bird regained its full power of flight, and rejoined others which are regularly fed by friendly men and women along the beach at Paekakariki.”

Fierce about cat control, Sanderson gave short shrift to any lurking feline. A 1939 newspaper article drolly described the ‘luck’ of a shining cuckoo exhausted from a long flight that had somehow contrived to land at the front door of the President of the Forest and Bird Protection Society. After resting for half an hour the bird flew away. But, the reporter surmised, had this been the home of a cat lover – rather than Captain Sanderson – doubtless the bird would have been eaten. At one meeting of the Forest and Bird Protection Society, President Sanderson suggested, presumably with tongue-in-cheek, that members concerned about killing kittens could take them out to Paekakariki!

A morepork also wintered over at 15 Pingau Street. According to Sanderson, “The bird has proved much more skilful than a cat in killing mice and rats. After the morepork has been in its cosy winter quarters for a week no rodents are caught in the traps which are always left set for them where birds cannot be harmed.”

Non-native birds, particularly that odious Ocker intruder, the ‘Australian Shrike’ (magpie), were unwelcome at Te Kohanga. One of Sanderson’s concerns was the decline in ‘pipit’ (Pihoihoi) numbers in the Wellington district, usually attributed to “the depredations of hedgehogs”; but, he cautioned, another invader was also at fault having witnessed “magpies attacking pipits on a number of occasions along the coast between Wellington and Paekākāriki.”

While living in Paekākāriki, Sanderson continued to spend three days a week on Society business, remaining in control right up until the time of his death. After failing to heed his own warning to change immediately out of cold, wet clothing, he developed pneumonia. According to his widow, Val was still working on various bulletins in his final days, before being taken to Wellington Hospital where he died a couple of days later on 29 December 1945, in his eightieth year.

Val was survived by Nellie and their two young daughters. Nancy, who was only eight years old when her father died, told of how she and her older sister Ruth spent a lot of time with him, “potter[ing] in the garden of their family home in Paekakariki on the days [he] wasn’t in Wellington on Forest & Bird business.” She described how, “You would walk up the path at night and the birds would arise with a deafening flutter and the path had to be scrubbed constantly. Starlings used to come to roost and we had some quite rare native birds; long-tailed cuckoo, tui, bellbirds, fantails and wax eyes. And we had wekas, until someone left the gate open.” Nevertheless, her father “could be quite a difficult man temperamentally…There were very firm rules in the house. We weren’t allowed to cut toetoe because it was a native plant.”

The Sanderson daughters went to Paekākāriki primary school where they would receive thruppence for every new child they signed up to the Society. They could also name “every native tree as we only had native trees in our garden.”

Little appears to have changed since in Sanderson’s Pingau Street garden. An article published in 1975, thirty years after Val’s death – when his 75-year-old widow was still living in the house – notes that “No house is visible and the thick forest of native bush entwines above the pathway. The house stands above the path and emerges suddenly. Over it, as if in protection, hang miro miro, puriri, Raukawa, taraira, kawakawa, pohututukawa, and ngaio crown grown from seed by Captain Sanderson, like the other trees on his section.”

Geoff Roberts, Paekākāriki paperboy at the time, perhaps best captures Captain Sanderson’s world at 15 Pingau Street:

In 1973, Forest & Bird held its 50th jubilee celebrations. On 28 March 1973, a ceremony was held at Paraparaumu beach to unveil a commemorative plaque in honour of Captain Sanderson. A quotation on the plaque reads: ‘He loved the birds and did much to make Kapiti a bird sanctuary.’ According to one report, “Kapiti Island looked beautiful across the water, and it was an eventful occasion with the wife of the founder, Mrs V. Sanderson, and her daughter and grandson, Justin, there.”

In the same year, Roy Nelson, then President of Forest & Bird, paid tribute to Captain Sanderson:

“Long before most men he [Sanderson] realised what was happening to lovely New Zealand and he set out to awaken the people to the need for real efforts to be made to protect and preserve the wonderful heritage we have in New Zealand. He steadfastly kept at this task as long as he lived.”

Nellie Sanderson, Val’s widow, continued to live at 15 Pingau Street until the 1980s. On 15 October 1997 she celebrated her 100th birthday in Auckland, dying in 2002 at age 104.

100 Years: Celebrating Captain Sanderson’s Life in Paekākāriki, April 2023

In March 2023, Forest & Bird launches a yearlong celebration of its centenary. As part of paying tribute to Val Sanderson as a founding father of modern-day conservation, in April volunteers from Ngā Uruora Kāpiti Project are organising the official opening of Sanderson’s Way in the restored Waikākāriki Wetland, Paekākāriki. The weekend’s events will include an exhibition celebrating local conservation in the village where Sanderson lived and worked while running Forest & Bird.

Meanwhile there is a strong case to be made for the street Sanderson’s cottage sits on to be renamed. Pīngao is a sand-binding seagrass found only on sand dunes in Aotearoa; Pingau Street is built on sand dunes. There appears to be no evidence to suggest the name Pingau has relevance to Paekākāriki. Consideration therefore ought to be given to consultation regarding renaming. A precedent for this is the recent renaming of Haumai Street to Haumia Street, after Ngāti Haumia, Paekākāriki mana whenua hapu.

Acknowledgments:

Dave Johnson; Forest & Bird; Kāpiti by Chris Maclean and Papers Past

For a fully referenced PDF of this article, please contact Judith on [email protected]

Paekākāriki.nz is a community-built, funded and run website. All funds go to weekly running costs, with huge amounts of professional work donated behind the scenes. If you can help financially, at a time when many supporting local businesses are hurting, we have launched a donation gateway.