Paekākāriki poet, Helen Heath, just won big time at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards for her poetry collection, Are Friends Electric? Here she chats to two other local poets, Maria McMillan and daughter Lily McMillan.

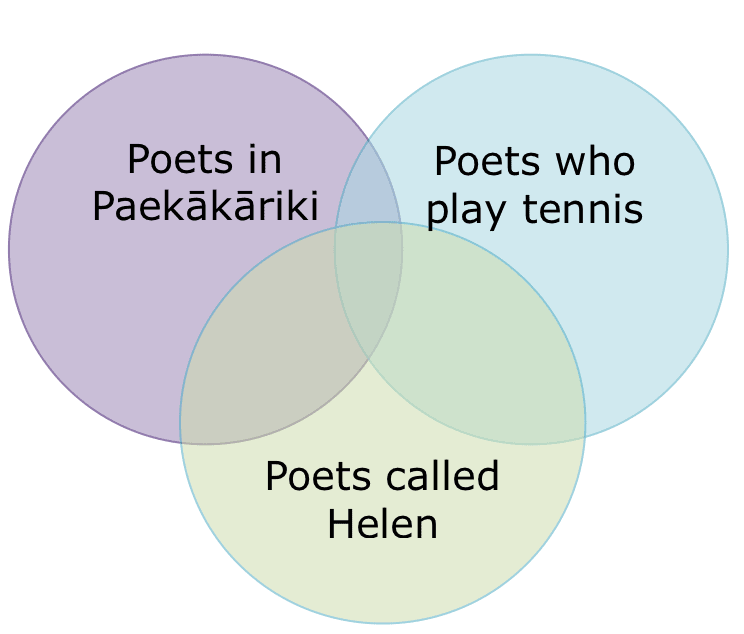

MM: So, Helen, congratulations. You’ve done yourself, your writing community and the village proud. Speaking of the village do you reckon we have the most poets per population (PPP) of anywhere in the country? There’s at least three of us in the tennis club alone. I mean, is there a standard way to measure this? Should it appear on LINZ reports like the level of doggishness stats and flooding risk?

HH: Thanks so much! It certainly does feel like we have more people writing poems than reading them sometimes! I don’t know about a standard measure, but I’ve been told that a collective noun for poets is a Helen of poets.

MM: That was Joe’s [Maria’s partner’s] assumption based on good logic. We definitely need a Venn diagram which includes Poets called Helen and Poets in Paekākākariki. Do you know of anyone else who is both?

HH: That would require some research!

MM: I’m liking your exclamation marks! Do you use them much in your poetry?

HH: Lol, sometimes, when I’m feeling frisky.

MM: Exclamation marks are like the opposite of restraint, eh? A big banging Look At Me signal from a line. I feel like every workshop I’ve been in somehow touches on restraint. What we should tell and not tell and when it might ever be acceptable to use an exclamation mark when a full stop might be more subtle. How do you manage restraint in your work, Helen?

HH: I think that when I first started writing poetry seriously, I was very afraid to be seen as writing excessively. It was seen by my teachers as a weakness. I trained myself to be extremely restrained. My poems were short and crystalline. I thought that was the epitome of good writing.

Now I think that kind of writing is just one way of writing well. Now I feel that I want to take up more space on the page. Women are told from childhood to restrain and restrict themselves in all areas of their lives — don’t be over emotional, don’t get fat, don’t be bossy — all that shit. I’m over it.

My first book has lots of short poems, but my latest book starts to spread out over the page. My next book will be prose, it will be the personal as political.

MM: That’s really interesting. I wonder if Are Friends Electric? is a book pushing between tensions in other ways. Not just restraint and, shall we say, generosity, but also the tension between political/philosophical investigation and personal revelation.

HH: Yeah, in my first book, Graft, I was deliberately thinking about science and the domestic as not being separate, also science and art, science and magical thinking. I wanted to depict science as being integral to everyday life, domestic and public.

Are Friends Electric? (VUP, 2018)

Graft (VUP 2012)

In the second section of the book (we’ll get to section one later) you’ve channelled really personal stories, grief stories, into this crazy-ass narrative of — how do you describe it —the mechanical prolongment of a man’s life as experienced by his would-be/is-she widow? I am sure you have a much better explanation. Anyway, is that a tension, the metanarrative of ideas about the world and power and the intimate small story? Or is that just old-school binary thinking?

In Are Friends Electric? I am still interested in social aspects of science, and I am still interested in the point at which two seemingly disparate things converge, but this time, instead of science and magical thinking, the convergence point is between technology and the human body.

So, the small scale, intimate, ‘womanly’ ideas and experience is inescapably intertwined with big philosophical ideas and interactions with technology. For me, anyway.

I think that the public/private divide is an artificial construct. For example, when workers who are also parents feel they need to act as if they have no family. That sucks.

MM: I agree, totally sucks. And when people believe that the arts of birthing and raising kids and grieving, the relationships between lovers and friends is domestic, and the writing about those things is ‘domestic’. Whereas I would flip that and say there is nothing more central, that’s where the yank of life happens…

HH: YES! The domestic is where it is all at!

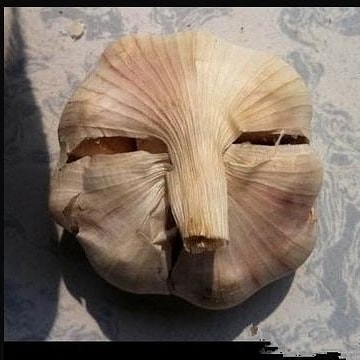

Sundays are for farmer’s markets and #facesinthings

Sundays are for cleaning the car and #facesinthings

Sundays are for packing lunchboxes for Monday and #facesinthings

Sundays are for recovering from parties and #facesinthings

Helen’s Instagram version of domestic life

MM: Hey, Lily has some questions for you now. She’s asking them to me too as part of a can-do project at school on the history of poetry in New Zealand.

LM: Hello. I was wondering, what’s your favourite style of poetry?

HH: Hi Lily. I like poems that have big ideas in them and make you think. But I also like them to have fun with words and language too.

LM: When did you get your first book published?

HH: I got my first book published in 2009, it was a little chapbook. That’s a short book with about 20 pages, rather than a full-length book. I was almost 40 years old, so I took a long time. I think if I was starting out today as a young poet I would make poetry zines and self-publish right from the start — have fun.

LM: What is your favourite poem that you wrote?

HH: My favourite poem that I wrote is… Oh that’s hard! In my first book I have a poem that is a maths equation, which I think has been under-appreciated. In my latest book I like the poems that used Greg Kan’s text randomiser, specifically the one called ‘Greg and the Bird’. I like that one because I put the whole book into the randomiser and then created one poem from the results. So, it is the whole book condensed into one crazy nonsense poem that kind of makes sense, haha.

LM: Who is your favourite poet (not yourself)

HH: My favourite poet, hmmmm… Well, your mum’s poetry is very cool. I also like Anne Carson, Deryn Rees-Jones, Robert Hass. Paula Green is about to put out a very cool book of poems for kids, you should have a read of that! I like lots of poets!

MM: Thanks Lily! So, to give people who haven’t read your book yet some context, the first section, seems to me anyway, to be touching on points of technological development. Not necessarily at the moment of invention, but representative of invention. From the opening poem that talks about the invention of writing (I love that you include this), through sexbots — or are they blow-up dolls? And weird Victorian pornographic peep shows, and Theo Jansen’s wonderful Strandbeasts (creatures he built that are powered through wind), through cosmetic surgery. I love seeing those particular things lined up in that way. First, are you comfortable with that description?

HH: Yeah, I wanted to demonstrate that the way we respond to technology hasn’t really ever changed. There has always been fear of new technology and the change it may bring. Often those fears are unfounded. However, I think it is really important to have discussions and debate around new technology so that we are approaching the use of it with our eyes open. I don’t think technology in itself is bad but I think it can be used for bad things — in warfare, for example.

MM: Many of the aspects of technology you focus on are developments where I reckon women have got the raw end of the deal. They seem to be avenues to promote and privilege certain men’s ideas of women and what they should be, over real women.

HH: I think technology is a lens that can amplify cultural aspects, sex-bots are one example of this. A strange, distorted idea of female sexuality represented as ever consenting and passive. But people make these things happen, technology doesn’t.

I do think that diversity of people creating technology will help change this and bring diversity and therefore different experiences of realities — more complexities. This needs to happen in parallel with stronger regulation of corporations.

So, poetry is a way of engaging people with big ideas and trying them on for size. We can have a public conversation about what we want the future to be like through speculative writing. Like big public thought experiments.

MM: I keep coming back to one poem in that first half, Run rabbit. Tell me about that poem. I am, while delighted by it, a bit mystified.

HH: I wrote that poem after visiting Christchurch a few years ago. The city was still quite raw from the earthquakes and the people I stayed with were obviously very affected. I had a dream I was visited by a ghost. All the things in the poem are quite real to me. I watched a YouTube clip of someone walking around the city with Google Glasses and the buildings were still there in Google Street view, but they jumped about due to a glitch. All these things came together for me and I guess I was spooked and that feeling probably comes through in the poem?

MM: Yeah it’s fabulous. I love the ending so much… In my sleep/a troubled young man is haunting me, he moves/ things about the room, prods me awake,/the furniture disappears. He wants me to know/all these things, to take note.

It feels like you’re answering that ghost throughout that book. Observing, thinking, noting.

Your book is full of references, interpretations of others’ interpretations, there are footnotes, and embedded quotes and found poetry. It’s not so much a direct raw engagement with the real world, as it is an engagement with how the raw world has been engaged with.

Maybe like a text full of hyperlinks. A kind of Wikipedia of a book?

HH: Yes, I read David Shield’s book Reality Hunger while I was writing the collection and I was thinking a lot about remix culture, about anxieties around originality, and how there’s nothing new. Reality Hunger is a book made up entirely of snippets from other texts but the way they sit next to each other, and form a whole, creates a new narrative and a commentary on the source material.

MM: I think you have done that beautifully. And while you do use a lot of other sources, it is an entirely new beast. The history you tell of technology, and of humanity, and the interplay of the two, is totally unique. What you choose to tell and not tell, and how you arrange the story reflects a 1970 baby, a writer, a feminist, the woman occupying the body of Helen Heath in the first decades of a new millennium. Tell it, but tell it slant someone said. As if there’s not always a slant.

HH: Yes, and being in a body is so important to this collection. During my creative research I began to wonder: Do we need a body to ‘know’ the world and to express that knowledge? To what extent can the human body (including the brain) be changed and advanced by medical and technical intervention? What consequences do we face as this occurs?

My creative work is influenced by the move in artificial intelligence towards the concept of ‘embodied embedded cognition’, which states that intelligent behaviour is a result of interactions between brain, body and environment. The construction of self is a very feminist topic!

“…since technology and gender are both socially constructed and socially pervasive, we never fully understand one without also understanding the other”*

Perhaps women in general are more aware about being in their bodies due to periods, self monitoring, social monitoring. I like Judith Butler’s take on gender as a social construct – the idea that every morning when we get dressed and/or put on make-up, we construct a self.

MM: Yeah, it’s so complex now, as there are so many women, like in an extreme instance, the women opting for plastic surgery in your books, who are ‘choosing’ to buy into and comply with imposed beauty standards. Some of them may claim it’s feminist to make this choice. But when women are monitored like you say, and their success so widely measured based on their level of compliance with beauty standards, how much is it free choice?

Hey, thanks for making time to chat Helen. One final question…ARE friends electric?

HH: Yes, I think they are! Nice talking to you Lily and Maria.

Read Run rabbit

*Lohan, Maria, and Wendy Faulkner. “Masculinities and Technologies Some Introductory Remarks.” Men and Masculinities 6.4 (2004): 319–329. jmm.sagepub.com. Web