Judith Galtry writes on the life in Paekākāriki of her late friend, the prolific author Frances Cherry. Frances and her whānau’s life in the village from the 1960s on reveals many a story about Paekākāriki‘s rich social history.

“Linda stood on the viewing platform and looked down at Parrot Bay. The houses and strips of road were more like a model than a real township. To the west the expanse of sea seemed to go on forever, and the island looked so small. Beyond the houses miles of park and sand-hills curved into a narrow, tree-covered point, stretching out into the sea.” from Washing up in Parrot Bay (1999)

In her innovative, lesbian, spiritualist novel, Washing up in Parrot Bay those people who knew Frances Cherry are aware that Parrot Bay is a fictitious name for her beloved Paekākāriki (the perch of the green parrot).

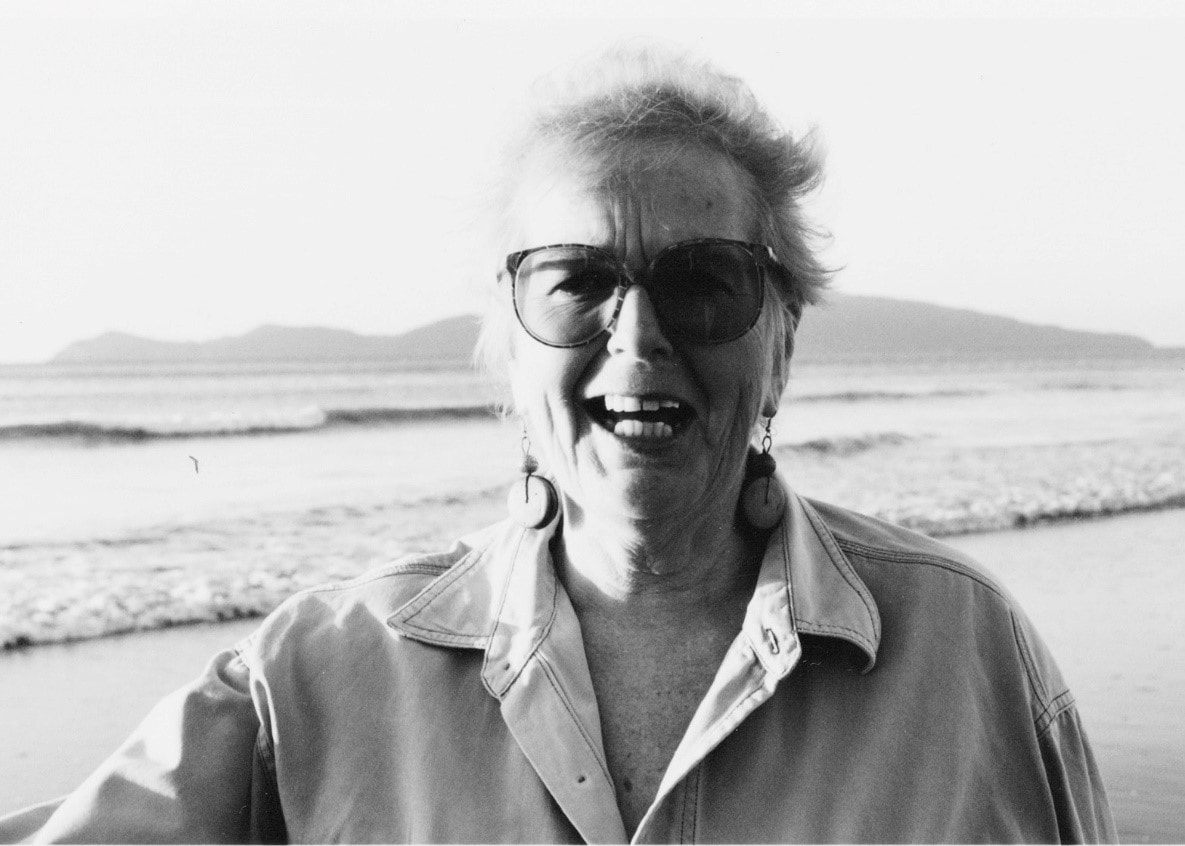

Frances Cherry was a New Zealand writer and author of a raft of books and short stories. Although she was ambivalent, at least in later life, about being labelled as a particular type of writer, much of her work is feminist. It is aimed primarily at women, tackling the often-thorny themes of marriage, motherhood, divorce, lesbianism, and widowhood. Later, Frances’ junior fiction series addressed the challenges of parental separation, custody and step-parenting. Unafraid to explore the often dark, emotional undercurrents of diverse relationships and ways of living, her stories have a therapeutic quality.

Paekākāriki was close to Frances’ heart, her spiritual home, her tūrangawaewae. It was where she lived as a young married woman, raised five children, and helped run various family enterprises with her husband, Bob Cherry. It was also the home, in their later life, of her parents, and her younger sister. It was to Paekākāriki that Frances returned as an older woman, before making what was to be her last move: back to the Wellington suburb of Kilbirnie where she had grown up. Even in Rita Angus Retirement Village, she still spoke longingly of Paekākāriki, of how she might stage a return, while knowing full well this was no longer a possibility. Yet, she continued to enjoy tales of village life until Parkinson’s disease overtook her at the end.

Birth and childhood

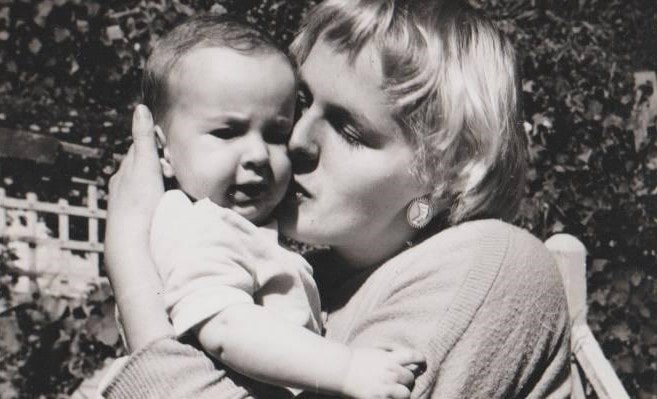

Born on 25 November 1937 in Wellington to communist parents, Connie and Albert (Birchie) Birchfield, Frances was set for an unusual life. For starters, her mother was almost 40 years old when she had Frances; old, especially in that era, to give birth to a first baby. Not surprisingly, Frances was an especially cherished and coddled child.

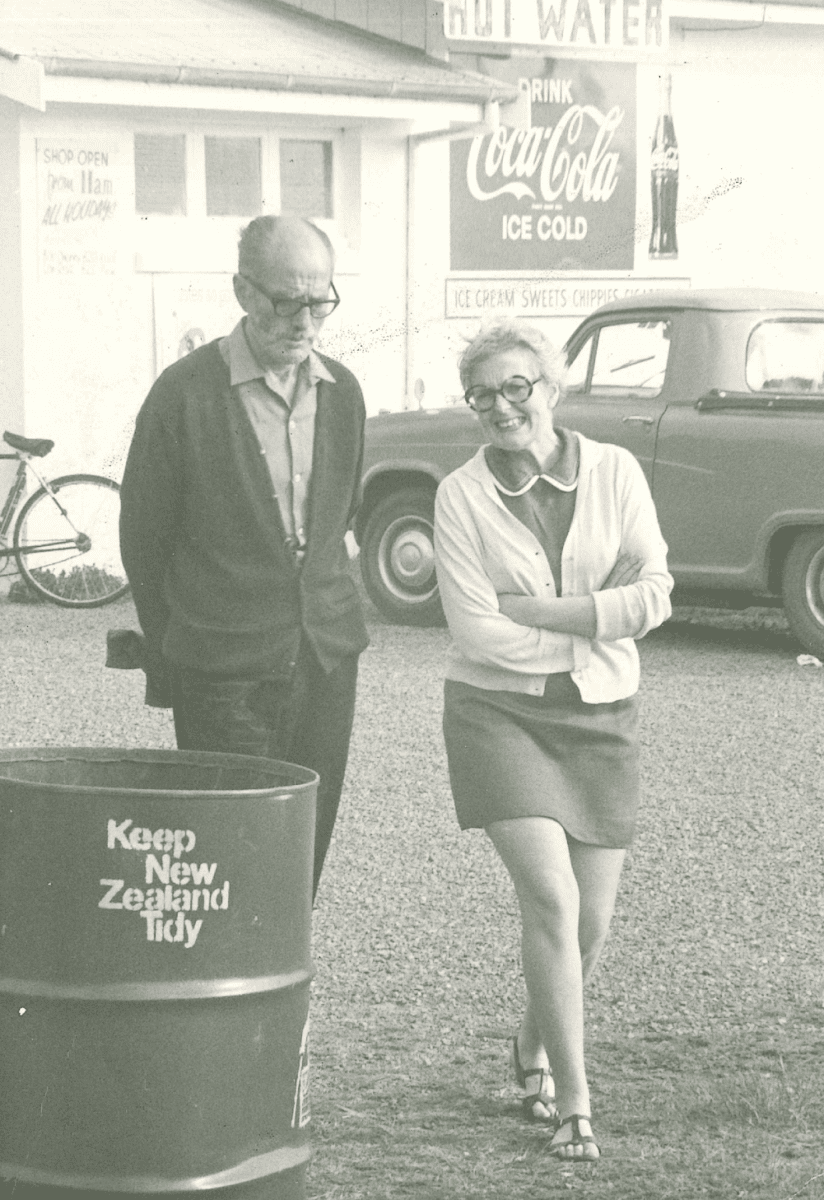

Frances’ sister, Maureen Birchfield, wrote a fascinating biography of their mother called She dared to speak: Connie Birchfield’s story. Connie emigrated from Lancashire to New Zealand where she became involved in unions and the Labour Party, joining the Communist Party in the 1930s. In Wellington, she was a well-known identity: a soapbox orator and agitator. But, for her daughters, Connie was a source of immense mortification. Seeing her communist mother standing on a soapbox in Courtenay Place was Frances’ “most embarrassing moment”, closely seconded by the sight of her father selling the People’s Voice on Cuba Street.

Like Connie before her, Frances’ later political concerns came under a wide umbrella of local and national issues. Frances took these lessons forward into her own life: how to be political, how to have a voice, how to be visible, how to be heard. Along with her mother’s milk, Frances imbibed a sense of political agency: the importance of making a difference.

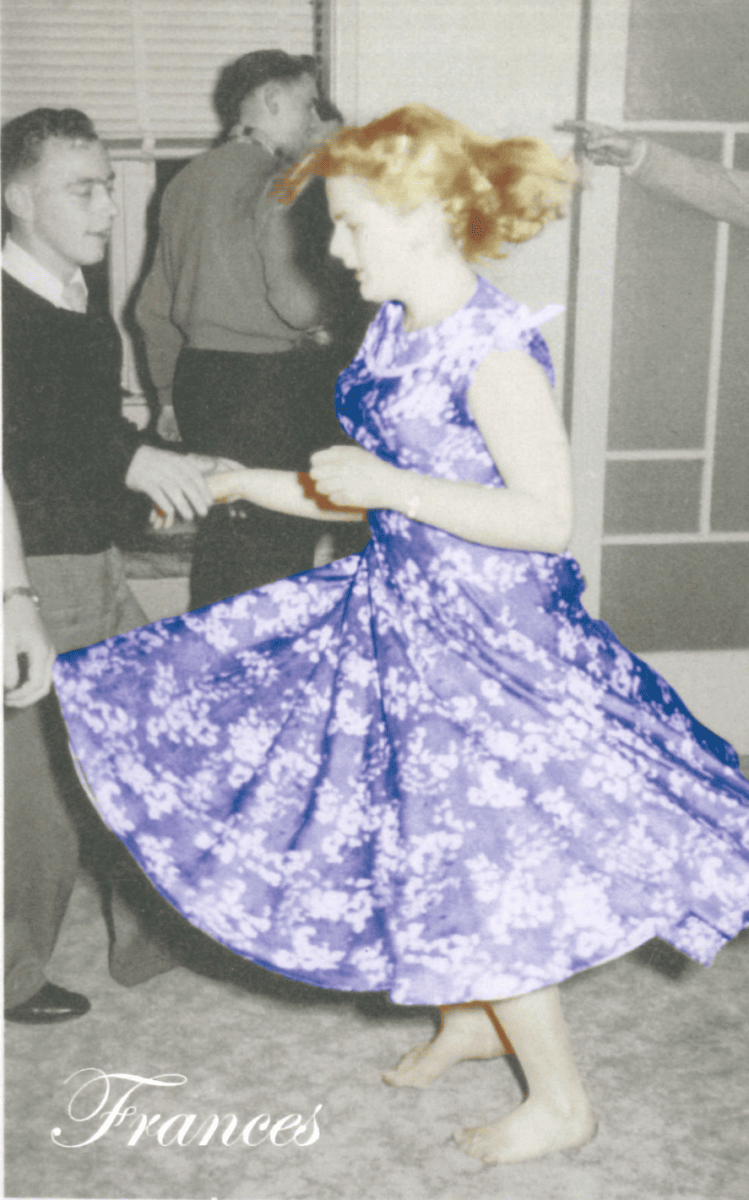

Frances’ activism did not manifest however until she was much older. By her own description, she was a “normal, self-obsessed, and self-conscious adolescent”. Later, as a kind of party trick that never failed to make people laugh, Frances would read aloud passages from her teenage diary: a dramatic account of the feelings and activities of an expressive young woman.

A reluctant student, Frances was more interested in friends, dancing and boyfriends, falling desperately in love with a blond haired, blue-eyed and married American sailor from the icebreaker Northwind, that docked in Wellington Harbour in September 1957. Frances even took her Yankee mariner, Don, home to meet her communist parents, who politely welcomed this representative from the heart of capitalism. Decades later she contacted him only to find, to her disappointment, that he was a rabid Republican and supporter of the United States’ president George W. Bush – as far from her own political leanings as was possible. This story, with its suggestion of a rekindled, late-in-life, but unlikely romance, became more tragi-comic with each retelling.

Paekākāriki round one: marriage & children

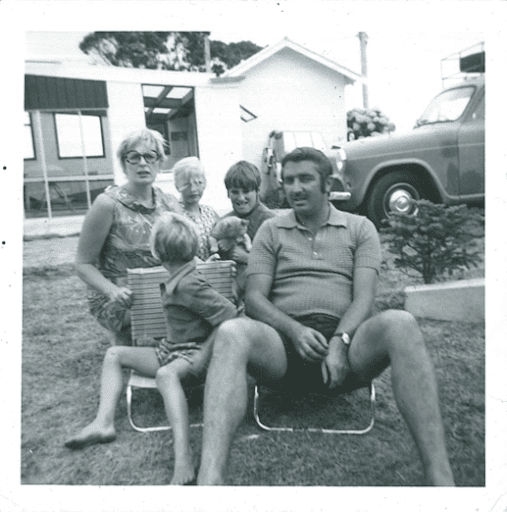

In September 1958, Frances married a Tasmanian man, Robert Hume Cherry. Those Paekākāriki old timers who remember the larger-than-life Bob Cherry are a dying breed. Darkly handsome and impossible to overlook, Bob stood taller than most people around him in stature and presence, as well as in assets and achievements. A small-town property magnate, Bob soon became known, not always flatteringly, as ‘Mr Paekākāriki’. Like most big personalities he had a multitude of friends and supporters, as well as his share of detractors.

Bob’s swagger may have partly reflected his Australian heritage: a one-man diaspora from that land to the west where most creatures are bigger, brighter and noisier.

Frances and Bob tied the knot at the tender ages of 20 and 23 respectively in St James church in Newtown, Wellington, in a ceremony presided over by a ‘left-wing parson’.

After a time living in a bleak, cold Wellington flat, Frances and Bob drifted incrementally northwards: first to Plimmerton, then to Pukerua Bay, before finally alighting on Paekākāriki in 1966. By then they had four young children in tow: Brent (born in 1959), Craig (1961), Jane (1963) and Robert (1965). Caitlin, the youngest, was born seven years later in 1972.

The Mission House, a large homestead at the top of the hill in Tilley Road (now Mira Grove) built by Paekākāriki’s early settler Smith family – and later a sanctuary for Open Brethren Church missionaries on sabbatical – became their nest. Just a short walk down Ocean Road were the glistening sea and Ocean Road steps: a social hub in summer.

In stark contrast to the Cherrys’ own grand property were the railway cottages further north on Tilley Road: the once subsidised housing for the often large and hard-up families of men who worked for the railways. Sadly, these whānau have long since gone, as part of New Zealand Rail’s privatisation.

Hot on her heels, Frances’ parents moved to Paekākāriki in 1968 buying No. 55 Wellington Road, then “a bachy little place with a long section that ran alongside the Sand Track that led from Wellington Road to the beach.”

A typical day for Frances was spent doing housework, shooting the breeze with other housewives over coffee, and gas-bagging on the phone, but always conscious there might be flapping ears on the party line. The telephone exchange was in the Post Office building on Beach Road:

“There was a telephone exchange in Paekākāriki and everyone was on a party line. We had a big box on the wall with a handle to turn so many times to get hold of people. Ours was something like two long rings and one short turn of the handle. Sometimes people would listen to other people’s calls (you could hear them breathing) and the women (only women of course) at the exchange would often tell us where Mrs So and So was – ‘She’s gone shopping in Paraparaumu’.”

Tipene O’Regan, then a teacher at Paekākāriki school, and his wife Sandra were close family friends, and the junior O’Regans and Cherrys often played together.

The Cherrys, along with Bob’s business partner, owned a large chunk of Paekākāriki: a small TAB, the grocery store, the vegetable shop, the Belvedere motels on the main highway next to the Europa service station and the neighbouring villa – another Smith family settler homestead (later converted to the 1906 Restaurant) – as well as a septic tank company called Spick and Span.

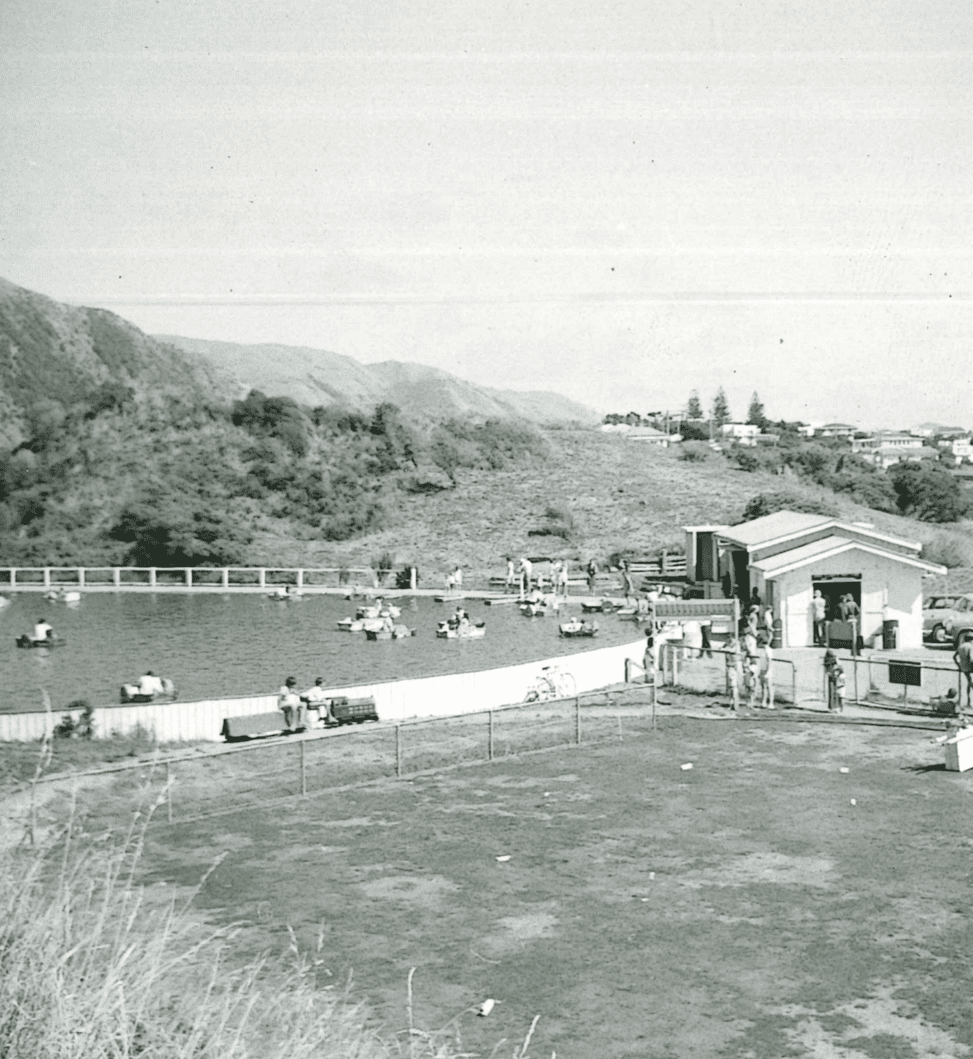

In the early 1970s, Bob and his partner took over the management of the boating pond, putting green, and shop in Paekākāriki’s Queen Elizabeth Park, later adding trampolines, a merry-go-round, a chair-o-plane, and a miniature train. Frances and the children helped run the complex.

Reflecting their social aspirations, Bob bought himself a black Austin Vanden Plas Princess and a crimson pink, two-door Austin Marina for Frances.

As Frances’ stories depict, she had mixed feelings about motherhood. She started a group for mothers with young children, before throwing herself into Playcentre, then held in the tennis club rooms, eventually becoming its president. Although her love for her children was never in doubt, Frances chafed at society’s restrictions, judgments and expectations. It was the judgment of other mothers that she dreaded the most.

Later, when she left her own marriage for life in the city, she imagined a sense of schadenfreude among those Paekākāriki friends whom she suspected of being trapped in unhappy marriages: a feeling that finally this cocky family who ruled the village from their roost on Mira Road had got ‘their just desserts’. Maybe this is why, later, she rejected any form of feminism that subscribed to the simplistic binary of ‘good women / bad men’.

But, at the time, Frances loved Paekākāriki as she knew so many people there. At one stage, their home became ‘Party Central’. Frances told of how late one night she lay drunk with a neighbour on Tilley Road looking at the stars, without a thought to traffic of which there was little then. And every Guy Fawke’s night, along with many other Paekākāriki-ites, the Cherrys went to Perkins’ farm where there was a bonfire.

“Paekākāriki was the world and Bob was king of it”, wrote Frances. While initially proud of her husband, Frances became increasingly conscious of the envy their lifestyle inspired; how some people viewed them as a kind of Paekākāriki royalty or mercantile elite because of the size of their house and Bob’s many business interests. The children suffered too. Frances’ older daughter, Jane, tells of being called a ‘rich bitch’ and chased home from Paekākāriki school.

As she drove around in her crimson car, Frances experienced self-doubt. Was this marriage a form of rebellion against her upbringing and her mother’s avid dislike of what she regarded as greedy capitalists who exploit others: those people who made Connie’s ‘blood boil’? Although Frances understood Bob’s showing off was a reaction to his childhood, her memoir records her growing embarrassment over hearing him telling people what he owned. Her pride in her husband was on the wane.

Bob’s friends called him the Tasmanian Devil. According to Frances, “He was a devil of a kid and a devil of an adult.” Frances weighed up leaving – there was no Domestic Purposes Benefit payments until 1973 – and secretly hoped that Bob might desert her so she would be left with the house.

Doubts aside, Paekākāriki was a paradise for the kids.

“They could wander more or less where they liked, climb up the hills, and swim at the beach…Paekākāriki was a real community where everyone knew each other. Many were involved in the school, playcentre, tennis club, bowling club and surf club. Also there was St Peter’s Hall, which was hired out for films, concerts and sometimes plays – and the shops where people caught up with each other.”

Much like today, in fact.

The pub was a different story. It was the one Paekākāriki institution that Frances bitterly resented because it stole her husband away from her and the family. Hooked on the masculine company, the big talk, and the booze, Bob would come home only after closing time, which, thankfully, was at 6pm in the early family years.

In Dancing with strings, Frances wrote: “Some people complain that New Zealand is an uncivilised country because the pubs close at six o’ clock but all [I] can think of is how much worse it would be if they were open later.’ However, on 9 October 1967, New Zealand introduced 10 o’clock closing and “All my fears came to fruition. Now Bob went to the pub every night when he finished work and I never knew when he was coming home…”

Much later, lamenting the Paekākāriki Hotel’s demolition in 2005, Frances wrote a poem, which was published by the Dominion newspaper.

In 1972, following the birth of their last child, Caitlin, Frances had run out of excuses for putting off writing. She went to a WEA writing class run by Fiona Kidman, then to VUW Sunday writing workshops. As became her style, her stories sympathetically addressed those often silent, but insufferable, situations in which people can find themselves.

In ‘About Janice’ she writes of the girl who does badly at school, unable to do her homework due to her parents’ fighting and forced to clean up after her father and his boozy mates each night; while ‘Nothing to Worry About’ evokes the alienation and dissociation of a woman she had read about in the news who had killed her children. Here, as so often in her writing, Frances took something deeply shocking and made it relatable: “I wondered what had caused her to do it. I wanted to write a sympathetic story. Even though my life was nowhere as bad as hers, a lot of the feeling of waiting, worrying and hoping was.”

Despite the apparent irony of the communist daughter wedded to the wealthy capitalist, Frances had not completely abandoned the values of her childhood. In the mid-1970s, along with Ames Street resident John Cox, she stood as a Labour candidate for Kāpiti Borough, promising to represent the needs of Paekākāriki. She believed it was important that a woman stand but ended up doing so herself when nobody else put themselves forward. Frances’ catch-cry was ‘Pick a Cherry at Election Time’. Unfortunately, their bid was unsuccessful, but Frances was pleased to get 200 votes.

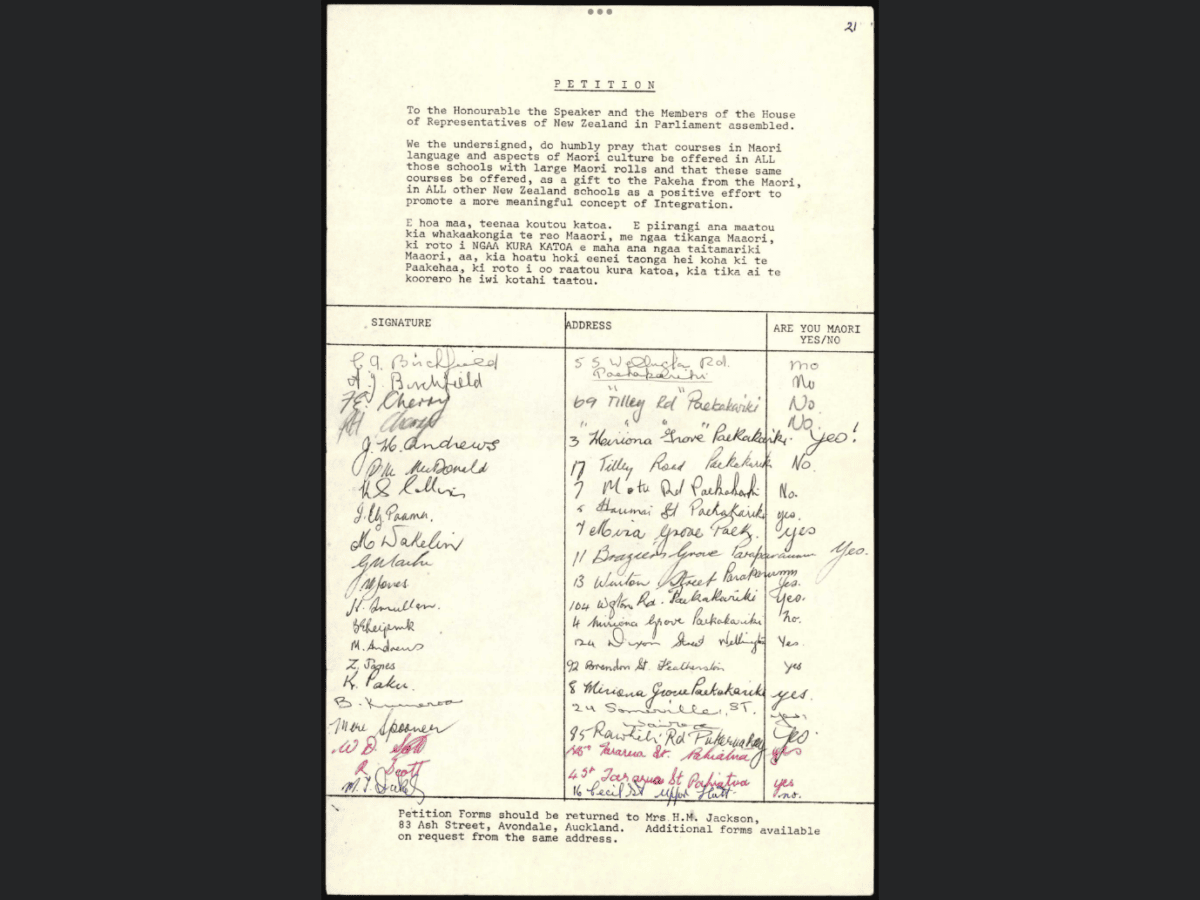

In 1972 Frances signed a petition to Parliament calling for the promotion of Māori language and culture in schools. Other Paekākāriki signatories included her parents (the Birchfields) and Jean Andrews (Ngāti Haumia, Ngāti Toa).

The murder that shook the nation

In March 1975, Paekākāriki hit the national headlines in an event that struck fear and horror into the hearts of local residents and seared itself into the national consciousness. At a time when murder was uncommon in Aotearoa, Queen Elizabeth Park became the scene of one of the country’s most shocking killings.

Newly married Gail McFadyen was staying in a caravan at Paekākāriki camping ground with her husband Graham while they were having a house built elsewhere. On 17 March, Gail saw her husband off to his new teaching job at Kāpiti College. When Graham came home, Gail was nowhere to be found. The police interviewed every person in Paekākāriki separately, including the entire Cherry family. Gail’s body was later discovered in a sandy grave in Queen Elizabeth Park off a track near the surf club. Frances recalled what a “terrible time it was with people imagining all sorts of things; many thought that [an old local] had killed her because he was often seen standing up on the road watching the girls on the beach.”

A groundsman at the Park, John Murphy, was eventually convicted of her murder. Mike Bungay was the lawyer for the defence, later including the case in a book about killers he had represented. In a strange twist of fate, Bungay’s wife, Ronda, subsequently became one of Frances’ close friends.

The end of Frances’ marriage

Bob turned forty in 1975, but that year fell sick with the heart disease that eventually killed him. Like the Tasmanian Devil, his nickname, Bob was an endangered species. Refusing to heed medical advice to rest, he was quickly back at work and the pub.

The Cherry union had effectively ended by 1978. The commencement of DPB payments in 1973 now offered an economic alternative, although limited, to marriage. If ever there was a time for exiting wedlock, it was now. In her memoir, Frances writes tellingly of her own and her husband’s dalliances. Following a local liaison, Bob visited his family in Australia. Here he met his new wife, bringing her and her daughter back to Paekākāriki to a house in Ames Street, only to return before long to Australia. But, in 1981, Frances received news that felt “as if someone had thrown a concrete block into my diaphragm.”

Only 46 years old, Bob had died unexpectedly from myocarditis – some might say from a broken heart from the devastation wreaked upon the family by the ending of the marriage. Later in life, any early bitterness having dissipated, Frances reflected on the good parts of their marriage, wondering if she and Bob should have “stuck things out” for the sake of their children.

At the time, though, Frances had to summon all her courage to turn her back on her wedding vows and on the small town of Paekākāriki where she imagined disapproval at every turn. ‘Selfish’ is what she supposed they called her, but that was not going to hold her back.

“I didn’t want to be in Paekākāriki any more. I wanted a new start where I could go forward without pain. Everybody knew your business in Paekākāriki and if they didn’t they made it up. I wanted to be in a place where, if I went to the supermarket, the staff didn’t know anything about me. I felt as if all eyes were upon me when I went down to the village. I wanted to be anonymous.”

Frances knew she would lose friends along the way, but she still possessed the golden gift of being able to make new ones at the drop of a hat.

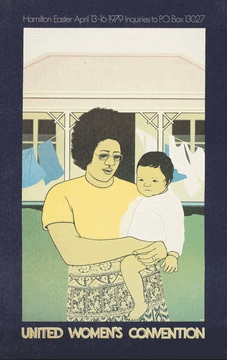

This middle stage of Frances’ life was life changing. In the 1970s and early 1980s feminism was flourishing in Aotearoa. At Easter 1979, she went to the United Women’s Convention in Hamilton where she was exposed to radical feminist ideas and met other women who had left, or were in the process of leaving, marriages.

One of around 2500 attendees, Frances was deeply influenced by her time at the Convention, with its workshops on everything from abortion to workplace discrimination. She found the conference both liberating and scary: she made new friends but, as the mother of sons, felt conflicted about the exclusion of men.

Around this time, Frances bought a house in Brooklyn, took up with a much younger woman, Wellington lawyer, Barbara Buckett, and threw herself wholeheartedly into the lesbian world. Cross-pollination with Paekākāriki continued – close friends and family still lived there – but the village now felt far too small.

Lesbian politics and homosexual law reform became a big part of her life. Along with various lesbian and gay friends, she celebrated the passing of the Homosexual Law Reform Act in 1986.

This period of Frances’ life, just over a decade, is best told in her close-to-the-bone novel Dancing with strings, published in 1989, and described as “the first lesbian novel published in New Zealand.”

Paekākāriki round two: late-life adventures

By the start of the 1990s, finding herself single again after an exciting, tumultuous, and writing-filled decade, Frances was restless. The Paekākāriki magic was once more at work. In 1991, in the grip of intense nostalgia, she visited a friend there, “It was a beautiful day and I thought I just have to live there again.”

It took a while to find something, but in May that year she bought 51 The Parade, a small villa one house back from the beach up a long driveway. “It was a pink and grey house, not very exciting from the outside but easy to maintain.” Having bought the house from an old woman in her nineties, Frances cross-leased it and sold the back part of the long section.

The Widowhood of Jacki Bates – mostly written in Shannon while living in Janet Frame’s cottage – was published in 1991, the year Frances moved back to Paekākāriki. This book explores emotions and behaviour both in and after a relationship ends: themes close to her heart following the death of Bob and the end of her other significant relationship with Barbara Buckett.

By the time of this move back to the wild sea and looming hills of Paekākāriki – the home of her mother, her sister and close friends – Frances was in her mid-fifties.

“I loved the anonymity of Wellington but after a while I missed the very thing I thought I hated about Paekākāriki. It’s nice that people know who you are. It’s a special place, it gets in your blood, no matter how far away you go.”

The sea still sparkled or roared depending on its mood, but Paekākāriki’s social landscape was now different from her early family phase. The village was rich in lesbian life, drama and literature. Alison Laurie, an old Wellington East Girls’ College friend, lived close by on The Parade. Alison had written a history of lesbianism in New Zealand and, along with journalist Julie Glamuzina, co-authored a lesbian take on the notorious Parker-Hulme matricide, the ‘brick in a stocking’ murder of Honorah Rieper by her daughter and her daughter’s friend in Christchurch in the 1950s.

Then, in 1994, Peter Jackson’s film Heavenly Creatures based on the ‘gymslip murder’ was released. Shortly after the film’s release, Paekākāriki-based journalist, Lin Ferguson, unmasked the United Kingdom-based crime writer, Anne Perry, as the rich-girl killer, Juliet Hulme. Frances believed the tipoff came from her own conversation with Lin, a near neighbour on the Sand Track. With an eye to the story’s Shakespearian dimensions, Frances later expressed mixed feelings about her disclosure, fearing the publicity that such exposure would inevitably attract while simultaneously regretting not being acknowledged as the source.

Various stories exist about the origin of the clue to Juliet Hulme’s new identity. Lin Ferguson claims she uncovered Anne Perry’s identity by doing “research in the local library and in a who’s who of authors and found the gossip to be true.” Peter Jackson reportedly begged Lin not to ‘out’ Anne Perry, but his plea was disregarded in the interest of such a juicy scoop. Perry herself later claimed that this disclosure was “the best thing that could have happened because now I feel free.”

In her diary written at the time of the murder, Frances records that the Parker-Hulme killing was particularly shocking, because it was committed by schoolgirls “the same age as me” who “even when they were caught, [they] didn’t seem to care.” Frances later claimed that the killing of the poor mother, Honora Parker, who ran a Christchurch fish and chip shop, demonstrated Juliet Hulme’s “rich-girl sense of entitlement” – it would have been fairer to have done away with both mothers!

Another lesbian friend, Victoria University economist, Prue Hyman, and her partner, Pat Rosier (ex-editor of the feminist mag Broadsheet), lived nearby at 66 Ames Street in poet Denis Glover’s old house. Later, the subject of Denis Glover became vexatious for Frances, with Denis displaying, even in death, a propensity to provoke shenanigans.

The 1990s proved to be a productive but tough decade for Frances. She now refused to be pigeonholed or defined by any sexual orientation, although she suspected that some lesbian friends saw this as a sellout. She told friends she just wanted to be herself, unapologetically and frankly Frances. She was keeping all options open so she could be free to choose her own destiny.

Short stories were pouring out of her. Various anthologies including New Women’s Fiction (1998); In Deadly Earnest (1989); Subversive Acts (1991); Erotic Writing (1992); and 100 New Zealand Short Stories (1997) contain several of her stories from this time.

Frances now dedicated herself to her writing, in addition to her family, friends and animals. Too often romantic relationships, with all their difficulties and drama, had proved disappointing. With a renewed sense of discipline, she adopted a rigid routine which allowed her to spend the best part of the day writing: “At 6.45 every morning I went for a walk with my poodle Dragon Lady. We went along the beach and through Queen Elizabeth Park towards Raumati South.”

Frances’ energy levels may have dimmed, but she was now free to do as she liked. Her children were grown and self-sufficient and Paekākāriki friends, both old and new, surrounded her. Annabel Fagan, a friend from her Brooklyn days, with whom she co-authored a book of short stories Double Act, now lived in Horomona Road. Always ready to initiate social activities, Frances started a book club around this time.

In May 1994, her mother died in Wellington Hospital following a short illness. The funeral was held at Paekākāriki’s St Peter’s Hall, on 13 May 1994 and a photograph of the procession accompanying Connie’s white coffin down Wellington Road to the hall featured in the following day’s Dominion.

Exacerbating her sense of loss, Frances was at the hospital visiting her dying mother when a car hit and killed Dragon Lady near the Sand Track. Frances kept the dog’s body at home for a day so people could visit. Her last poodle – little, black Chloe – later became her loyal companion for many years.

Paekākāriki controversies: a fallout over Denis Glover

In the mid-1990s, Paekākāriki’s creative community was rocked by controversy over how to best commemorate a past resident: the legendary poet, Denis Glover. Frances found herself in the thick of the action.

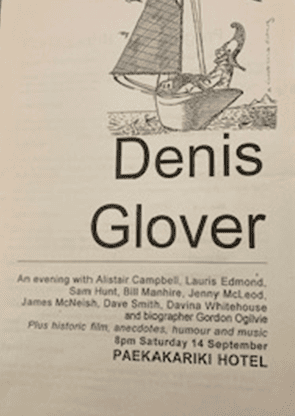

In 1996, sixteen years after Glover’s death, the Paekākāriki Community Arts Trust, of which Frances was a former member, organised an event at the Paekākāriki Hotel to celebrate the poet’s life and works. An impressive line-up of poets, writers, musicians, old friends and neighbours, as well as Denis’s biographer, Gordon Ogilvy, came together to read poems both by and about Glover.

In anticipation of this occasion, Frances interviewed Paekākāriki locals who had known Denis for a booklet, Friends and Neighbour: Denis Glover in Paekākāriki. There are a mix of tales, some show Glover’s kindly aspect – always ready for a chat, dishing out gardening tips, helping lift the heavy lid off the playcentre sandpit – while others emphasise his darker side: a drunken Denis lying unconscious in the gutter in Ames Street.

But, as the event came closer, the committee and others in the community disagreed over the portrayal of the brilliant, but hell-raising, Glover. Not everyone was happy for the stories that Frances had gathered to be recounted, especially those tales that depicted the inebriated mischief, misdemeanours and misogyny for which Glover was notorious, including towards his deceased and, herself, sometimes incendiary partner, Khura Skelton.

There was concern that a focus on Denis’s less savoury side – a side which seemed to intensify in his later years – would detract from his significant achievements.

Feelings ran high over the booklet, but Frances maintained that any attempt to whitewash Denis – who never hesitated to tramp where angels feared to tread – was wrongheaded. For was not Denis and Khura’s relationship notoriously fractious and would not Denis – who was only too aware of his own deep flaws and compulsion to shock – approve of, even wish for, a realistic depiction of himself?

In the end, Frances was not allowed to sell her booklet on the evening; nor were any of its anecdotes to be read aloud. A letter (dated 21 October 1996) to a friend highlights her feelings at this time:

“I hope you enjoy the little booklet. It actually caused quite a controversy in our community…He [Denis] had a passionate relationship with Khura and I feel that many of the things he did after she died were because of grief and denial that she was dead. The booklet was printed to be sold at the evening but at the last minute I wasn’t allowed to do that. I also discovered that sanitised excerpts were not to be read out at the evening, as I expected, and only discovered this when I arrived at the pub…” [She concludes] “Paekākāriki is a wonderful place in many ways, though with all the trouble I have had over these anecdotes I began to think it was too isolated and thought of leaving. I have got over that now…”

Frances was clearly hurt at being misunderstood and sad to lose some close friendships through this process.

A decade later, Caryl Hamer, the publisher of Friends and Neighbours wrote in Paekākāriki Xpressed (the local rag) that while the decision to print Frances’ booklet was controversial, in the end they backed her view that it was important to portray the “warts and all poet.”

The Glover hullabaloo shows that Frances was not scared of controversy. But while this time it was the depiction of Glover under fire, Frances did not shy away from writing about her own less-than-noble inclinations. In her memoir, she described her fantasy of murdering her husband by “tying cotton (because it wouldn’t be easily seen) across our verandah steps so [he] would trip and fall down to the creek.” Not really wishing for this to happen, she instinctively recognised the cathartic value of such an outlandish admission.

Frances’ writing tended to be affirming and normalising. Her acknowledgement that being human necessitates the juggling of often contradictory emotions, including or especially towards loved ones, was one of her great strengths. For instance, spelling out the bleakness of postpartum depression is her description of sitting in Wellington’s Pigeon Park with her first baby and her mother: “What now? I’d married the handsome prince and had a baby. The future seemed like no future. Also, the thing that hit me was that I couldn’t change my mind. For the first time in my life I couldn’t change my mind.” It was this honesty, as much as her authorial advice, which drew people – some who never left – to her writing workshops. For many aspiring writers, these workshops doubled as therapy.

On 25 November 1977, Frances turned sixty. Photographed on the back of a friend’s motorbike, she set out to show that she did not intend to slow down with age.

Family and other frictions: Washing up in Parrot Bay

All families have frictions and fissures, and Frances’ family was no exception. Her third and last adult novel Washing up In Parrot Bay (1999), became a source of sorrow as it affected, for a time, her relationship with one of her daughters.

Described as a “provocative and engaging black tragicomedy” featuring “lesbians, witches and man-free conception rituals,” Parrot Bay is a quintessentially Paekākāriki novel.

The many evocative images of Parrot Bay describe Paekākāriki and its multiple moods:

“He was in Parrot Bay before he realised it, turning across the railway line and driving through the village where familiar people wandered. The sea sparkled as he drove over the rise and down on to the esplanade. A few figures were strolling on the beach. Seagulls dived at the water, and surfboard riders floated like black dots, waiting for waves…[He] looked at the island, silent and full of secrets.”

And, in an allusion to the legendary Rumbling Tum Hot Bread Shop (of the 1990s) in Holtom’s Building next to the railway tracks, “Adele sat on the high stool in the Gurgling Belly takeaway shop, watching trucks and cars pass by over the railway line…It was a blustery grey day with a threat of rain, depressing after all the sunshine they’d had.”

But Washing up In Parrot Bay also reflected Frances’ ambivalent feelings about Paekākāriki, including its insularity and, sometimes, inward-looking bent.

” ‘She was normal at one time’, he said. ‘What went wrong?’ ‘Dunno… It’s probably living here. This place would send anyone crazy.’…‘I mean the whole place. Parrot Bay. It’s so insular. I couldn’t bear it.’…‘There are some very interesting people living here. Writers, artists, all sorts.’ So there, he thought. ‘Each to their own’.”

Also, the sea – still the source of so much pleasure – now seemed more threatening. “Along the beachfront the wind blew their hair back from their faces. They looked down at the waves crashing and booming on the sea wall. The sea was supposed to be rising with the greenhouse effect. It was all quite worrying…”

In 2002, these mixed feelings would drive Frances away from Paekākāriki once again, first to Waikanae, then to Petone for three years, and finally back to Kilbirnie in 2006. “The taxi dropped her in the middle of the city. She stood, dazed, as the lunchtime throng jostled around her. Nothing mattered any more.”

Regrettably, the publication of Parrot Bay led to a short-lived rift between Frances and her older daughter. Originally conceived as a co-authored effort with the inventive Jane – who developed the spiritualist, witchcraft and turkey-basting components that lend the novel its contemporary edge –the novel was published under Frances’ name alone. Jane’s extensive contribution is acknowledged at the front of Parrot Bay, but Frances was clearly conflicted.

In her memoir, published almost two decades after Parrot Bay, Frances ruminates, “When [Parrot Bay] was ready to go to print, I told Roger [Roger Steele, the publisher] that I wanted Jane’s name on the cover as well, but he felt that it would be too hard to market a novel with two authors, and to my great regret I gave in. I do not blame him; I only blame myself and am deeply sorry. I should have insisted.” A review in the Sunday Star Times at the time describes Parrot Bay as “provocative and engaging”, noting “[It] would be a shame for it to be pushed into a pigeon-hole labelled lesbian-only lit. For the broad-minded looking for an energetic and interesting read, there is plenty to enjoy.”

Much later, in 2018, Roger and Frances were to collaborate again, this time on the publication of her memoir, To be perfectly Frances: a memoir. Although Frances intended this to be a mostly positive summing up of her life and contribution to writing, she experienced huge angst in the publication process, a kind of re-run of the Parrot Bay experience. Family members and friends warned her that her portrayal of certain events and people might not be appreciated by the living, but Frances decided to proceed anyway.

Bob was dead so could not be defamed but significant others from Frances’ past were alive and kicking. As the memoir came closer to completion, Roger advised her that it would be wise to run certain sections past key potentially recognisable individuals so they could be modified, if necessary. On his advice, she had already made significant changes to render certain characters unidentifiable, even changing an individual’s age, hair colour and pet.

One person nevertheless sought advice from a barrister specialising in media law who claimed that, in order to publish, she would have to expurgate sections of text on the grounds that anyone who knew Frances could identify who she was writing about, regardless of the changes made to their identity. As such, it was defamatory, in the barrister’s opinion. Moreover, contended the legal eagle, writer and publisher had committed, even if unwittingly, a ‘breach of privacy’ by previously passing the manuscript to reviewers who were acknowledged at the front of her memoir. Roger and Frances chose to comply with these requests and no further action was taken.

For Frances, herself a teacher of memoir, this process threw into question the nature of memoir, autobiography and biography, especially whether they can be meaningful once key identifiers have been altered to such an extent that an account becomes, in effect, a work of fiction. The genre of auto-fiction involving the deliberate amalgamation of non-fiction and fiction in a memoir was then in its infancy and also ran counter to Frances’ preference for authorial directness and honesty. For Frances, this painful process confirmed that her interpretation of reality could never again be approached as the only legitimate viewpoint.

The bossy older sister

Back in Paekākāriki, Frances was living close not only to her parents, but also, later, to her younger sister, Maureen. Both sisters were talented writers – Maureen of non-fiction and Frances of fiction – but were quite different in temperament and appearance. When young, they did everything together, but sibling tension is apparent in Maureen’s short story ‘Let’s talk about Me!’. This tale, which won the Friends of Kāpiti Libraries Festival Creative Writing competition in 2013 and was published in the Kāpiti Observer, appears to be based in fact for the “bossy older sister” has “Marilyn Monroe blonde hair and generous curves, five children, and several live-in partners of both genders.” In this narrative, Maisy, the protagonist, airs her main beef: “I never got much of a chance to talk about me. That’s because I had a bossy, older sister who always wanted to talk about herself. She always butted in if I started talking about me.”

Writing for young people

In the late 1990s, Frances morphed into a junior fiction writer. As with her adult novels, Frances’ stories for young readers resonate with emotional honesty, addressing big themes such as parental separation and custody, moving to a new place, death of a grandparent, and issues of betrayal and trust.

The first of these In the Dark, published in 1999, examines a custody dispute from the child’s perspective, with two Paekākāriki girls, Michaela Barr and Hester Callister, featuring on the front cover. The following year Leon was published and, in 2001, shortlisted in the New Zealand Post Children’s Book Awards. Paekākāriki’s Earl of Seacliff Art Workshop (run by Michael O’Leary) published Gate Crasher and Other Stories (2006). Flashpoint appeared that year, followed by Kyla (2009) and Pay Back (2017).

Frances: animal lover, activist, teacher & friend

Alive to the wonders of the natural world, including the animal kingdom, it did not take long for Frances’ conversation to turn to her pets. Each pet was heavily anthropomorphised, especially the last one – Kilbirnie-based Ray: a grey-striped feline with what Frances described as “a devil-may-care attitude.” Based on her phone’s final voice message, a caller could be forgiven for mistaking Ray for an errant husband, coming and going as he pleased, rather than a mere cat.

An activist to her core, Frances became involved with local issues wherever she happened to be living. In Paekākāriki, she organised public meetings to protest Telecom upping its charging prices and became involved in a school debate; later, while living in Petone, she formed a local group to oppose a battery recycling plant operated by Exide.

Frances possessed a gift for friendship. Like most talents, it was facilitated by her own actions: her ability to take the social initiative. She sometimes claimed that shyness was a form of selfishness, describing how she grew out of being a shy child into a teenage clown through realising the power of making people laugh.

Frances set an example of how to live life. Although conscious of others’ perceptions of her, she knew she had to be true to herself, a lesson burnt in on the ending of her marriage. Often, she said things others might be thinking: an ‘emperor has no clothes’ response to the world that usually worked for her. Frances may not have been everyone’s cup of tea, but her propensity towards expressing her shadowy imaginings gave others the license to express their own less than charitable sides. This facility made Frances funny too, as in her imaginary tale of doing away with her husband – who could resist laughing at such an impossible fantasy expressed aloud?

Frances’ fiction has an undeniable immediacy and vibrancy. When considering her legacy, descriptions of Frances’ ‘undeviating honesty’ and ‘sense of wonder’ recur. Good friends, such as the author Marilyn Duckworth, and psychotherapist, Ronda Bungay, attribute these qualities with keeping her stories young and fresh; while for Roger Steele, who published two of Frances’ books, it was her ‘particular gift for making dialogue come alive’ that stood out. A prolific author, Frances has over fifteen books and short stories to her name (see Bibliography).

Even at eighty, Frances was still attracting newcomers and oldcomers to her writing groups. Dot Dyett, who was 100 years old when I talked with her in September 2023, was one of these workshop lifers. As part of an exercise set by Frances to write about their ‘first love’, Dot described the time in England during the war when she met a young Jewish man who had escaped Nazi-infested Europe; how they had cycled to a field where they lay together hand-in-hand, only to be savaged by ants having mistakenly spread their rug on an anthill. Dot reports that Frances became impatient with what she saw as her students’ “mealy mouthed accounts” and suggested they describe something more attention grabbing such as “****ing in the back of a car.” Not everyone could get away with saying these things.

But, in her final year of taking classes, Frances’ feedback no longer seemed as acute or insightful as before. Later, Dot wondered if this was due to the Parkinson’s disease that, then unknown to Frances, was starting to ravage her system.

But this is about Paekākāriki, a place close to Frances’ heart. Even in her last days at Kilbirnie’s Rita Angus Retirement Village, she sometimes yearned for her Paekākāriki days. The village exerted a push-pull effect on her, much like the tides of the beach she once walked each morning. When she needed freedom from the village’s confines she migrated south to the relative obscurity of the city; but when she felt lonely and lost in the universe, missing Paekākāriki’s landscape and characters, she came back. This was one of Frances’ contradictions, like the two sides of her personality: the hidden-away author fiercely guarding her writing time, and the gregarious, social animal who liked nothing better than time spent with family and friends, chewing the fat on any topic under the sun.

Later in life, Frances ruefully reflected on the changes to Paekākāriki. Recalling its past as a railway town with its own special sense of community, she felt that Paekākāriki had since become more like a satellite suburb of Wellington.

Throughout life, Frances found all sorts of people who met her great need for friendship. I was fortunate to be one of them. Informed by her love of reading and acute observation of life, Frances’ curiosity about the world made her a great companion with whom to discuss books and unpick the small events of life, the interactions, and inevitable argy-bargy of human encounter. I was struck by a piece written about friendship which seems to echo her thinking:

“[I]f you like to write and argue and criticize, the only basis for the importance of your general claims – those beyond your particular experience – is the fact that you are human, like everybody else. And humans need friends to act as sounding boards for ideas as much as for gossip. The trick… is simply finding the right person for it.” (Dean, Michelle. ‘The Formidable Friendship of Mary McCarthy and Hannah Arendt’. New Yorker, 4 June 2013).

On 24 April 2022, aged 84 years, Frances died peacefully at Rita Angus Retirement Village, surrounded by her family. Her obituary describes Frances best: “A unique, passionate and fiercely loving woman who was ahead of her time.”

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant from the Paekākāriki Community Board. I wish to thank Jane Cherry for sharing her mother’s correspondence and photographs with me. I also thank Roger Steele, who published some of Frances’ later work, for his generous and freely given feedback, and Sylvia Bagnall for editorial assistance. Finally, thanks go to Dave Johnson, Chair of the Paekākāriki Station Museum Trust, for his help and support.

All photographs, unless otherwise labelled, are from Jane Cherry’s collection.

Bibliography of Frances’ publications

Adult fiction

Dancing with Strings (1989)

The Widowhood of Jacki Bates (New Women’s Press, 1991)

Washing up in Parrot Bay (Spiral Collective and Steele Roberts, 1999)

Short stories

The Daughter-in-Law and Other Stories (New Women’s Press, 1986)

Gate Crasher (Earl of Seacliff Art Workshop, 2006)

Out of Her Hair and Other Stories (Earl of Seacliff Art Workshop, 2009)

Double Act: stories from Frances Cherry and Annabel Fagan (Earl of Seacliff Art Workshop, 2010)

Memoir

To be Perfectly Frances (Steele Roberts, 2018)

Children’s and young adult fiction

In the Dark (Mallinson Rendel, 1999)

Leon (Mallinson Rendel, 2000)

Flashpoint (Scholastic, 2006)

Kyla (Scholastic, 2009)

Pay Back (CreateBooks, 2017)

For a fully referenced PDF of this article, please contact Judith on [email protected]

You may also like to read:

Denis Glover: A Poet’s Life in Paekākāriki by Judith Galtry

The Last Years of the Paekākāriki Pub photos by Andrew Ross, text by Mark Amery

Paekākāriki.nz is a community-built, funded and run website. All funds go to weekly running costs, with huge amounts of professional work donated behind the scenes. If you can help financially, at a time when many supporting local businesses are hurting, we have launched a donation gateway.